As social animals, humans tend to form groups that can range in size from a few individual members to entire nation-states. Historically and through the present day, human groups frequently come into conflict. A noted feature of human intergroup conflict is the proclivity of ingroup members—that is, members recognized as being part of a particular group—to inflict harm upon those considered to be non-members who are part of an outgroup. A new study may help explain the motivation for this hostility. The study found that aggression directed at rival group members increases activity in certain brain regions that are associated with feelings of reward and pleasure. Investigating this potential link further could deepen our understanding of the origins of intergroup aggressiveness and suggest interventions for curbing group-based violence. See also: Aggression; Brain; Motivation; Sociobiology

The study, led by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University in the United States, involved the use of a technique called functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). This technique detects changes in blood flow within the brain. Increased blood flow in an area indicates increased activity by neurons, or nerve cells, in that region, with this increase in turn revealing which brain regions are most active during mental and physical processes. See also: Medical imaging; Neuron

The researchers recruited 35 male college student subjects and then had the subjects perform a competitive task commonly used in psychological studies. For this task, one research subject tried to press a button faster than another subject, with the loser of the contest receiving an unpleasant noise through a pair of headphones. The subjects were told that some of the opponents attended the same university and other opponents attended a rival university. In actuality, all subjects played against a computer, and no one inflicted noise on each other. As a gauge of aggression, the subjects could choose the volume level of the aversive noise on a scale of one to four seconds based on (fictitious) information about the volume level selected for them by their opponents. Another task, involving the passing of a virtual ball ostensibly between the subjects and members of the rival university, was also administered to evoke feelings of ingroup positivity and outgroup negativity. See also: Psychology

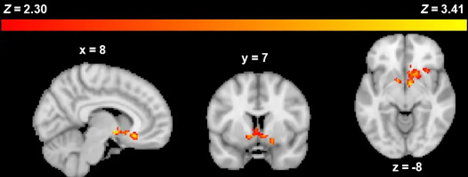

Overall, results showed that subjects who displayed more aggression toward outgroup members compared to ingroup members had higher levels of activity in the nucleus accumbens and ventromedial prefrontal cortex, both of which are part of the reward circuit in the brain. Other notable anatomical patterns included heightened activity in the frontostriatal circuit, which is involved in social cognition executive function, while subjects decided how aggressive to be toward opponents and during provocation by these opponents. These results suggest that learning more about neural mechanisms behind intergroup aggression could lead to the development of interventions that alter these pathways as a means of reducing human conflict. See also: Neurobiology