Studies have shown that all classes of vertebrates—and even some invertebrate species—have the cognitive ability to discriminate among different quantities. For example, many kinds of studied animals can distinguish specific numbers of objects in their environment. This mathematical skill is theorized to be important in wide-ranging animal behaviors such as herding, schooling, and flocking; choosing among mates based upon visual characteristics, such as number or size of stripes; and estimating amounts of food sources during foraging. Fewer kinds of animals, however, have been shown to possess the cognitive ability to perform addition and subtraction, which are more complex numerical tasks. To date, researchers have documented this arithmetical ability in primates and birds, as well as in spiders and honeybees. Now a new study has discovered that fish—specifically cichlids and stingrays (Fig 1)—can also perform addition and subtraction of a quantity of one in the number space from one to five. The findings are unexpected because neither species is known to have an obvious ecological or behavioral need for this mathematical ability. Furthermore, the findings emphasize that a neocortex—the part of the brain that evolved in mammals and had long been considered necessary for certain higher-level cognitive abilities—is not required for performing basic arithmetical operations. See also: Arithmetic; Batoidea; Brain; Cognition; Evolution; Fish; Mammalia; Mathematics

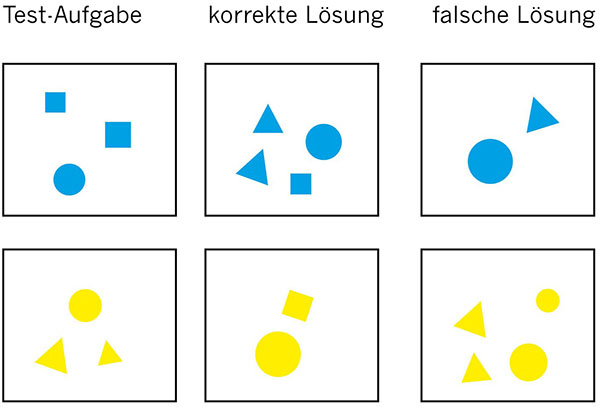

Researchers arrived at the results by performing experiments with eight cichlids (Pseudotropheus zebra) obtained from a commercial dealer and eight freshwater stingrays (Potamotrygon motoro) obtained from the Frankfurt Zoo in Germany. Using a projector, the researchers presented images upon the wall of a water tank holding individual cichlids, while laminated cards were used for the stingrays in a separate setup. The images consisted of geometric shapes—namely squares, triangles, and circles. The shapes were of different sizes and either uniformly colored blue or yellow. After showing the animals an initial image, the researchers then presented the fish with two additional images. These additional images contained one less and one more shape than the original image. With food offered as a reward, the fish learned to associate blue-colored shapes with the arithmetical operation of adding one, and yellow-colored shapes with the arithmetical operation of subtracting one. For example, a fish could be shown four squares in the initial image. Then, when presented with two additional images showing three and five squares, the fish learned to swim to the five-square image when colored blue, and the three-square image when colored yellow.

Not all the studied fish were able to grasp the arithmetical tasks, and each individual animal's results varied, suggesting a spectrum of cognitive ability. More cichlids were able to learn the experimental task than stingrays, but those stingrays that did learn the task performed better at it than the cichlids. Both species more quickly demonstrated an understanding of addition versus subtraction. Overall, the results indicate that fish share some of the same cognitive potential as better-studied mammals and birds, raising questions about these animals' other cognitive skills that have long been assumed to only be the domain of animals with larger brains and neocortices. See also: Addition; Animal; Subtraction