The diverse totality of microorganisms regularly found on and in the human body is collectively referred to as the human microbiota or microbial flora, with the largest microbial community in the body residing in the large intestine, or colon. Bacteria comprise most of the normal microbial flora, with fungi and protozoa making up a smaller contribution. Investigators have determined that any loss of health or fitness of microbial flora can be detrimental to the body, resulting in immunological dysfunction and disease. For example, individuals with chronic intestinal diseases—including inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn's disease, and ulcerative colitis—are subject to intestinal inflammation and mucosal damage, leading to losses of the intestine's beneficial flora. To restore normal intestinal function and repair tissue damage, treatment typically involves the use of antibiotics to kill harmful intestinal bacteria that may access the bloodstream. Concomitantly, these antibiotics also destroy some beneficial bacterial components of the intestine's microbial flora (previously diminished by disease-borne inflammation and tissue damage); however, the antibiotics do not affect the small percentage of fungal organisms in the microbiota. Thus, microbial fungi have opportunities to dominate mucosal niches of the intestine. See also: Antibiotic; Bacteria; Colon; Fungi; Gastrointestinal tract disorders; Human microbiota; Immune response in inflammatory bowel disease; Inflammation; Inflammatory bowel disease; Intestine; Microbiology; Microbiome

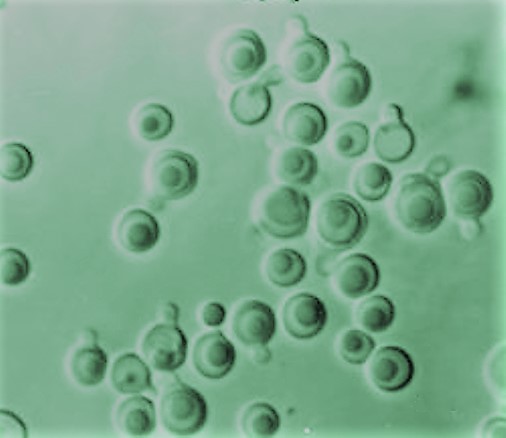

In experimental mouse models, researchers have observed that certain fungal organisms—particularly Debaryomyces hansenii (a yeast commonly used in food processing)—colonizing intestinal wounds in the absence of normal bacterial flora will, in fact, exacerbate intestinal inflammation and prevent proper wound healing. Debaryomyces hansenii is frequently used in food manufacturing for the ripening of various cheeses. It also is found in numerous processed meats, as well as many fermented beverages and foods. Furthermore, D. hansenii survives optimally at a pH of 4 to 8. Thus, it can survive well in the large intestine, which has a pH between 5.5 and 7. Food microbiologists have noted that foodborne D. hansenii invades inflamed and injured intestinal tissues and causes harm. Additional experimental evidence indicates that intestinal colonization by D. hansenii intensifies inflammation by specifically blocking molecular signals that otherwise would strengthen epithelial-cell proliferation, wound closure, and eventual wound healing. Most importantly, invading D. hansenii microorganisms only infect intestinal wounds and are absent in uninjured parts of the intestine. In follow-up studies, investigators eliminated the invading fungi through the use of antifungal medications, subsequently allowing mucosal restoration and normal wound healing. See also: Cheese; Food fermentation; Food manufacturing; Food microbiology; pH; Yeast

With these preliminary results, scientists are contemplating the importance of prescribing antifungal drugs along with antibiotics in the treatment of chronic intestinal ailments. In addition, dietary changes—especially the elimination from the diet of certain cheeses, meats, and other food products known to harbor D. hansenii—may improve intestinal wound healing in patients with chronic intestinal diseases. Scientists are planning a larger study in patients with Crohn's disease to see if there is a correlation between diet and the abundance of D. hansenii in the intestine. If a positive correlation is found, it is likely that dietary adjustments (to avoid foods with D. hansenii and possibly other fungi) and antifungal medications would become part of the medical armamentarium to prevent and treat chronic intestinal diseases. See also: Food; Medicine