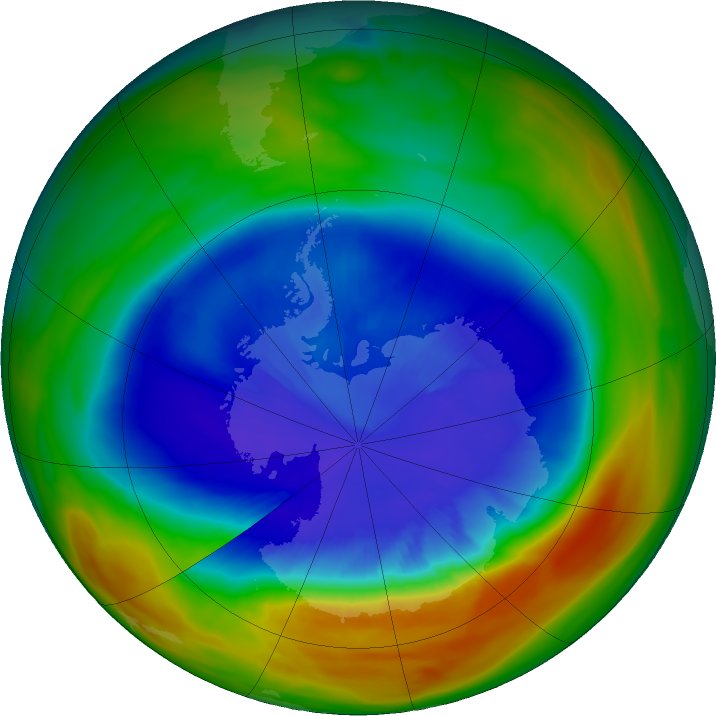

In 1987, the Montreal Protocol, the international treaty banning chemicals that deplete the ozone layer, was adopted. Thirty years later, NASA scientists reported in the journal Geophysical Research Letters (January 2018) satellite measurements showing decreased stratospheric ozone depletion as a result of declining levels of ozone-depleting chlorine from the breakdown of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs)—that is, chemicals that were used as solvents, refrigerants, and aerosol-can propellants. The ozone hole is an area of severely depleted ozone in the stratosphere over Antacrtica, appearing at the beginning of Southern Hemisphere spring (August–October). From 2005 to 2016, instruments aboard the NASA Aura satellite measured chlorine and ozone levels in the Antarctic ozone hole. As compared to measurements taken in 2005, the measurements showed about a 20 percent decline in ozone depletion during the Antarctic winter. This is the first study to confirm that the ozone hole has begun healing and that the recovery can be attributed to the implementation of the Montreal Protocol. See also: Antarctica; Halogenated hydrocarbon; Ozone; Stratosphere; Stratospheric ozone

Stratospheric ozone absorbs all of the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation of less than 290 nanometers (DNA-damaging radiation) and much of the UVB (290–320 nm) radiation, the harmful ultraviolet rays that cause sunburn, cataracts, and skin cancer, and harm plant life. Because CFCs are so slow to decompose in the stratosphere (long-lived compounds), even if the Montreal Protocol is followed as agreed upon, Antarctic ozone levels not are expected to return to levels measured in the 1950s until around 2080. However, had the Montreal Protocol not been ratified, by 2065 nearly two-thirds the Earth's atmospheric ozone would have been destroyed, according to NASA simulations. See also: Sun; Ultraviolet radiation (biology)