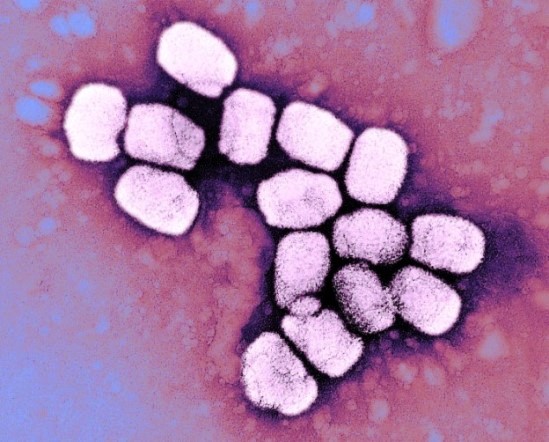

Over the course of history, smallpox has been among the most feared diseases of humankind. Caused by the variola virus (a DNA-containing member of the Poxviridae family) and spread by transfer through respiratory droplets during face-to-face contact, smallpox is an acute infectious disease, involving widespread skin lesions, often resulting in disfiguring scars on the face, and frequently leading to blindness and even death in about 30% of cases. Fortunately, through a successful global vaccination program, the disease was declared eradicated in 1979. Historically, though, the smallpox virus has been in circulation among human populations for about 3000 years. Notably, signature smallpox-like rashes and pustules have been identified on ancient Egyptian mummies from the third century BCE, and accounts of the disease have survived in written documents from China, Japan, and India dating to the fourth century CE. However, there is no written evidence of smallpox's existence in Europe prior to about the 11th century CE, which is when Europeans began travel to and from the Middle East during the Crusades. It was not until the 13th century CE that written evidence suggested the likely presence of smallpox among people living in central and northern Europe. Now, however, using DNA-sequencing methods on human skeletal and dental remains, investigators have identified the smallpox virus in DNA recovered from 11 Viking-Age individuals who lived in northern Europe between 600 and 1050 CE. See also: Anthropology; Archeology; Dental anthropology; Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA); DNA sequencing; Infectious disease; Molecular anthropology; Physical anthropology; Smallpox

In 2020, scientists at the University of Cambridge and University of Copenhagen undertook a comprehensive investigation to study and sequence the genomic material of more than 1800 human fossils from both Europe and the Americas. The researchers recovered sequences of DNA that matched those of the smallpox virus from 11 Viking-Age individuals. These 11 individuals were part of a larger sample of 500 Viking-Age individuals, indicating a 2% positivity rate—a sufficiently high rate to suggest that smallpox was already endemic across Europe by the late 6th century CE. This new genomic evidence is significant because it confirms that Vikings came into contact with the smallpox virus during travels to Asia and/or Africa, and then brought back the virus to Europe as early as 600 CE. Demonstration of the smallpox virus among Vikings who lived between 600 and 1050 CE in areas encompassing present-day Scandinavia, western Russia, and the United Kingdom is a remarkable discovery because it pushes back the presence of smallpox among European populations by about 1000 years. Besides assigning an earlier date for the presence of smallpox in Europe, the research also calls into question other suggested theories about the introduction of smallpox into Europe. For example, the results argue against the idea that returning Crusaders were the sole agents responsible for bringing smallpox to Europe. See also: Dating methods; Europe; Fossil; Genomics

Investigators are interested in how the smallpox virus spread geographically and epidemiologically because such information provides insight into how viruses travel among human populations over time and across continents. This is especially pertinent to understanding the COVID-19 pandemic, which has also swept around the world via individuals who traveled to areas where the disease was present and then returned home with the virus; or via individuals who remained home, but came into contact with infected persons traveling from other areas with the disease. See also: Epidemic; Epidemiology; Novel coronavirus is declared a global pandemic