A transit of the planet Mercury across the face of the Sun occurs on May 9, 2016, beginning at 11:12 GMT and ending at 18:42 GMT. It will be visible to anyone in a region of the Earth where the Sun is above the horizon during this interval. Observers in most of South America, eastern North America, western Europe including Scandinavia, northwestern Africa, Greenland, and other locations at high northerly latitudes can witness the entire transit. Part of the transit will be visible from the rest of the Americas, Europe, and Africa, and from much of Asia; in these regions the transit will be in progress either at sunrise or at sunset. This transit of Mercury will be one of only 14 to occur during the 21st century.

|

May 7, 2003 |

| November 8, 2006 |

| May 9, 2016 |

| November 11, 2019 |

| November 13, 2032 |

| November 7, 2039 |

| May 7, 2049 |

| November 9, 2052 |

| May 10, 2062 |

| November 11, 2065 |

| November 14, 2078 |

| November 7, 2085 |

| May 8, 2095 |

| November 10, 2098 |

In astronomy, a transit is the apparent passage of one astronomical object (such as a planet) in front of a second larger object (such as the disk of a star). It is therefore related to the phenomena of eclipses (in which the foreground object partially obscures the background one) and occultations (in which the foreground object completely blocks the view). See also: Eclipse; Occultation; Transit (astronomy)

Only two planets in the solar system can ever transit the Sun as seen from Earth: Mercury and Venus, which orbit closer to the Sun than Earth does. Moreover, transits of Mercury can occur only when that planet is passing through the ecliptic (the plane of Earth's orbit), which restricts them to roughly mid May and mid November. Transits of Venus are far less common than those of Mercury: After ones in 2004 and 2012, another will not happen until 2117. See also: Ecliptic; Mercury (planet); Planet; Sun; 2012 transit of Venus; Venus

The astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) was the first to predict a transit of Mercury, for November 7, 1631, but he died too soon to see it. Working from Kepler's report, his fellow astronomer Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655) thus became the first to observe the planet's transit. During a later transit of Mercury, on November 7, 1677, the astronomer Edmond Halley (1656–1742) came to the realization that it was possible to estimate Earth's distance from the Sun from measurements of planetary transits from different latitudes on Earth. A telescopic instrument designed specifically for observing transits was developed by the Danish astronomer Ole Roemer in 1689. See also: Astronomical transit instrument

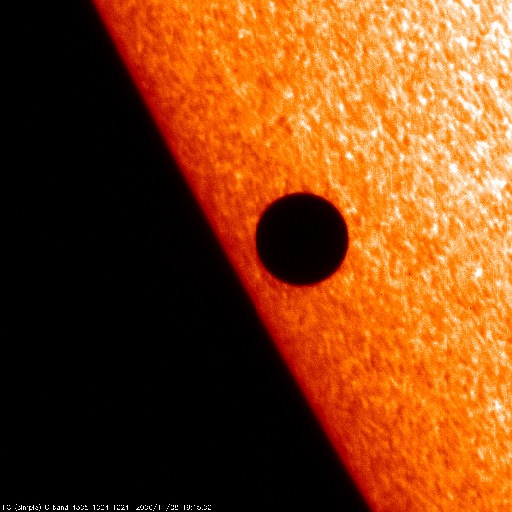

During a transit, Mercury will appear as no more than a tiny silhouetted dot less than 150th the width of the Sun. It can therefore be seen only with the aid of a telescope, but for safety reasons the telescope must be equipped with a solar filter or must project the Sun's image onto a screen or other surface. CAUTION: Viewing the Sun directly even for short intervals can cause permanent vision loss, especially if magnifying lenses or mirrors are used. See also: Telescope

In recent years, planetary transits have gained new significance in astronomy as in the search for worlds around other stars. Using the Kepler space telescope and other sensitive instruments, astronomers have scanned the light from other stars for small telltale dips in intensity that would signify the transit of an exoplanet across the stellar disk. The Kepler mission has identified thousands of candidate exoplanets by this technique, many of which have subsequently been confirmed to exist. See also: Exoplanet research; Kepler mission