Key Concepts

The attractive force that holds atoms or ions together. Chemical bonds are very strong. To break one bond in each molecule in a mole of material typically requires an energy of many tens of kilocalories.

It is convenient to classify chemical bonding into several types, although all real cases are mixtures of these idealized cases. The theory of the various bond types has been well developed and tested by theoretical chemists. See also: Computational chemistry; Molecular orbital theory; Quantum chemistry

The simplest chemical bonds to describe are those resulting from direct coulombic attractions between ions of opposite charge, as in most crystalline salts. These are termed ionic bonds. See also: Coulomb's law; Ionic crystals; Structural chemistry

Other chemical bonds include a wide variety of types, ranging from the very weak van der Waals attractions, which bind neon atoms together in solid neon, to metallic bonds or metallike bonds, in which very many electrons are spread over a lattice of positively charged atom cores and give rise to a stable configuration for those cores. See also: Crystal structure; Intermolecular forces

Covalent bond

The covalent bond, in which two electrons bind two atoms together (as in the compounds shown below)

is the most characteristic link in chemistry. The theory that accounts for it is a cornerstone of chemical science. The physical and chemical properties of any molecule are direct consequences of its particular detailed electronic structure. Yet the theory of any one covalent chemical bond, for example, the H  H bond in the hydrogen molecule, has much in common with the theory of any other covalent bond, for example, the O

H bond in the hydrogen molecule, has much in common with the theory of any other covalent bond, for example, the O  H bond in the water molecule. The current theory of covalent bonds both treats their qualitative features and quantitatively accounts for the molecular properties that are a consequence of those features. The theory is a branch of quantum theory. See also: Nonrelativistic quantum theory

H bond in the water molecule. The current theory of covalent bonds both treats their qualitative features and quantitatively accounts for the molecular properties that are a consequence of those features. The theory is a branch of quantum theory. See also: Nonrelativistic quantum theory

Hydrogen molecule

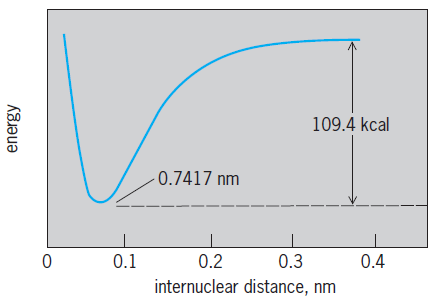

A brief outline of the application of quantum theory to the bond in the hydrogen molecule H  H follows. Here two electrons, each of charge −e, bind together two protons, each of charge +e, with the electrons much lighter than the protons. What must be explained, above all else, is that these particles form an entity with the protons 0.074 nanometer apart, more stable by D = 109 kcal (456 kilojoules) per mole than two separate hydrogen atoms, where D is the binding energy. In more detail, a molecular energy is involved (ignoring nuclear kinetic energy) that depends on internuclear distance, as shown in the illustration. This curve can be determined experimentally, and it can be used to interpret the characteristic spectroscopic properties of hydrogen gas. See also: Molecular structure and spectra

H follows. Here two electrons, each of charge −e, bind together two protons, each of charge +e, with the electrons much lighter than the protons. What must be explained, above all else, is that these particles form an entity with the protons 0.074 nanometer apart, more stable by D = 109 kcal (456 kilojoules) per mole than two separate hydrogen atoms, where D is the binding energy. In more detail, a molecular energy is involved (ignoring nuclear kinetic energy) that depends on internuclear distance, as shown in the illustration. This curve can be determined experimentally, and it can be used to interpret the characteristic spectroscopic properties of hydrogen gas. See also: Molecular structure and spectra

The quantum theory accounts for the properties of isolated atoms by assigning atomic orbitals for individual electrons to move in, not more than two electrons at a time. For the hydrogen atom, the orbitals are labeled 1s, 2s, 2px, 2py, 2pz, and so on, with 1s the one having the lowest energy. For the molecule H2 one electron, say electron 1, might be assigned to a 1s orbital on proton A, with 1sA (1) written to signify this; similarly electron 2 might be assigned to the same kind of orbital on proton B, written as 1sB (2). Since independent probabilities multiply and orbitals represent probability amplitudes, the description for the combined system shown in Eq. (1) is arrived at.

Unfortunately, this fails to account for the bond properties; it gives a binding energy of only 10 kcal (41.9 kJ) per mole. See also: Atomic structure and spectra; Exclusion principle

An essential defect of Eq. (1) is the numbering of the electrons; it puts electron 1 on proton A, electron 2 on proton B. Electrons cannot be distinguished experimentally, so they should not be given unique numbers; the function 1sA (2)1sB (1) would be just as good as the foregoing. It is necessary to use a description that is not affected by interchange of electron labels, as in the additive combination of Eq. (2).

(The difference combination also is an acceptable description, but it represents an excited state of the molecule.)

Any complete molecular electronic wave function should include electron spin. Symmetric space wave functions like Eq. (2) must be multiplied by antisymmetric spin wave functions to give total wave functions that are antisymmetrical with respect to interchange of electrons. For the ground state of hydrogen, and for the normal covalent bond elsewhere, this requirement means that the electron spins must be paired to give a total electron spin of zero.

The simple relationship described by Eq. (2) qualitatively accounts for the existence of the covalent bond; the predicted binding energy is D = 74 kcal (310 kJ) per mole; and the shape of the curve, with the minimum appearing at 0.080 nm, is right.

The description of Eq. (2) can be systematically improved. The charge acting on the electron may be changed from +1e to the larger value, +Ze, which is more realistic for the actual molecule. With Z = 1.17 this gives D = 87 kcal (364 kJ) per mole. Polarization effects may be introduced by taking Eq. (3),

where 1σA = 1sA + λ2pzA and 1σB = 1sB + λ2pzB . This gives D = 93 kcal (389 kJ). Ionic terms may be introduced, acknowledging the possibility that both electrons may be on one atom, by taking Eq. (4)

where C represents a constant. This also gives (with Z = 1.19) D = 93 kcal (389 kJ). Another possible approach is to include both ionic terms and polarization effects, and other terms involving 2s, 3d, 4f, and other orbitals. If this is done, eventually one obtains the observed D value and a potential curve that is in complete agreement with experiment.

The linear mixing of terms such as 1sA (1)1sB (2) is called resonance; the method of mixing covalent and ionic structures is called the valence bond (VB) method. The particular mixing coefficients can be found by the variational principle: The best values for such parameters are those that make the total energy of the molecule, properly computed from quantum mechanics, a minimum. The energy expression contains only terms that have a direct classical interpretation: the kinetic energy of the electrons, their energy of repulsion for one another, their energy of attraction for the nuclei, and the nuclear-nuclear repulsion energy. See also: Resonance (molecular structure)

Alternative descriptions of H2 are possible, of which the most important is provided by the molecular orbital (MO) method. Here electrons are put one at a time into orbitals that are spread over the whole molecule, usually approximating these orbitals by linear combinations of atomic orbitals (LCAO). For H2 the lowest molecular orbital is ϕ1 ≈ 1sA + 1sB , the next ϕ2 ≈ 1sA − 1sB . The simplest molecular orbital description is displayed in Eq. (5),

which represents an equal weighting of covalent and ionic structures; it gives D = 61 kcal (255 kJ) for Z = 1.00 and D = 80 kcal (335 kJ) for Z = 1.20. More suitable is a mixture of this function with the function obtained by promoting both electrons from ϕ1 to ϕ2. The result of this configuration interaction process has the form of Eq. (6),

and it is identical with the valence bond function of Eq. (4). In this manner more terms can be added, using more orbitals, until, again, the accurate potential energy curve is obtained.

The most accurate description known for the chemical bond in H2 is a very complicated electronic wave function. The calculated and observed values of D and other properties agree absolutely.

Complex molecules

The problem of the proper description of chemical bonds in molecules that are more complicated than H2 has many inherent difficulties. The qualitative theory of chemical bonding in complex molecules preserves the use of many chemical concepts that predate quantum chemistry itself; among these are electrostatic and steric factors, tautomerism, and electronegativity. The quantitative theory is highly computational in nature and involves extensive use of computers and supercomputers.

The number of covalent bonds that an atom can form is called the covalence and is determined by the detailed electron configuration of the atom. An extremely important case is that of carbon. In most of its compounds, carbon forms four bonds. When these connect it to four other atoms, the directions of the bonds to these other atoms normally make angles of about 109° to one another, unless the attached atoms are crowded or constrained by other bonds. That is, covalent bonds have preferred directions. However, in accord with the idea that carbon forms four bonds, it is necessary to introduce the notion of double and triple bonds. Thus in the structural formula of ethylene, C2H4 (

1

), all lines denote covalent bonds,

the double line connecting the carbon atoms being a double bond. Such double bonds are distinctly shorter, almost twice as stiff, and require considerably more energy to break completely than do single bonds. However, they do not require twice as much energy to break as a single bond. Similarly, acetylene (

2

) is written with a triple bond,

which is still shorter than a double bond. A carbon-carbon single bond has a length close to 1.54 × 10−8 cm, whereas the triple bond is about 1.21 × 10−8 cm long. See also: Bond angle and distance; Valence

In many compounds the rules for writing bond formulas are not unique. For example, benzene, C6H6 (

3

), can be written in two forms.

Evidence proves that all six C-C bonds are equivalent, so neither formula can be correct. The correct picture is a blend of the two, in which the bonds have many properties intermediate between those of double and single bonds but in which the whole molecule displays an additional stability. This resonance occurs whenever the structure is such that two or more different bond formulas can legitimately be drawn for the same geometry. See also: Benzene; Electron configuration

Many substances have some bonds that are covalent and others which are ionic. Thus in crystalline ammonium chloride, NH4Cl, the hydrogens are bound to nitrogen by electron pairs, but the NH4 group is a positive ion and the chlorine is a negative ion.

Both electrons of a covalent bond may come from one of the atoms. Such a bond is called a coordinate or dative covalent bond or semipolar double bond, and is one example of the combination of ionic and covalent bonding.

The hydrogen bond is a special bond in which a hydrogen atom links a pair of other atoms. The linked atoms are normally oxygen, fluorine, chlorine, or nitrogen. These four elements are all quite electronegative, a fact which favors a partially ionic interpretation of this kind of bonding. See also: Electronegativity; Hydrogen bond