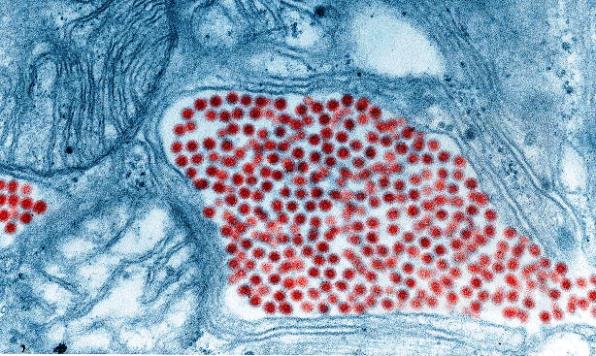

Eastern equine encephalitis is a rare infectious viral disease that primarily affects humans and equines (horses, mules, donkeys, and zebras). It is caused by a mosquito-borne virus (arbovirus) that is native to the eastern half of the United States, particularly in coastal regions. The virus also has been detected elsewhere in North America, as well as in South America and the Caribbean. Categorized as a zoonotic disease (that is, a disease transmitted from animals to humans), infected mosquitoes are the transmitting agents (vectors) responsible for spreading the virus that causes it. The virus predominantly affects birds—including chickens—which remain asymptomatic of the disease. However, Eastern equine encephalitis can be lethal when contracted by humans and horses because the virus can invade the central nervous system and lead to brain swelling and damage, which often results in death. As such, investigators are troubled by a recent dramatic increase in the detection of Eastern equine encephalitis virus in Florida. See also: Animal virus; Arboviral encephalitides; Economic entomology; Encephalitis (arboviral); Exotic viral diseases; Infectious disease; Mosquito; Virus; Zoonoses

In general, Eastern equine encephalitis virus flows between one specific type of mosquito (Culiseta melanura) and birds. However, because the Culiseta melanura mosquito does not feed on mammals, transmission of the virus to humans and horses is left to other mosquitoes (for example, those belonging to the genera Aedes, Coquillettidia, and Culex). These non-Culiseta mosquitoes contract the virus by biting infected birds; then, when these mosquitoes subsequently bite a human or a horse, they can transmit the virus, leading to disease. See also: Disease ecology; Epidemiology

Annually, Florida accounts for the highest number of cases of Eastern equine encephalitis in the United States. Transmission can take place throughout the year; in other locations, though, the virus is not transmitted during winter months. Horse cases number in the hundreds, whereas the incidence in humans remains low, with fewer than 10 reported cases per year (however, it is estimated that at least 50 human cases go unreported each year). Epidemiologists, though, are concerned with the appearance of Eastern equine encephalitis virus in sentinel programs in Florida, in which chickens are used as warning animals to identify the early presence of Eastern equine encephalitis (as well as a variety of other mosquito-borne diseases). Researchers have been taking weekly blood samples from sentinel chickens, which may have been bitten by mosquitoes carrying Eastern equine encephalitis virus, and testing the chickens' blood for antibodies to the virus. If the birds test positive for these antibodies, it means that the virus is being disseminated among the mosquito and bird populations. With an increase in positive test results for Eastern equine encephalitis virus among sentinels—as is the current case in Florida—the risk of transmission to humans would also be expected to increase. More than 150 chickens tested positive for the virus in 2018, and scientists are predicting a greater number of positive results in chickens in 2019. See also: Antibody; Human diseases spread by tick, mosquito, and flea bites are escalating

The monitoring of Eastern equine encephalitis virus through chicken sentinel programs in Florida should allow investigators to direct various control measures to reduce or eradicate the virus. However, although vaccines are available to protect horses against the virus, there are currently no vaccines approved for human use. Thus, humans should display vigilance and endeavor to avoid any contact with mosquitoes by undertaking preventative measures, including the use of mosquito repellents and the wearing of long pants and sleeves to limit exposed skin. See also: Public health; Vaccination