The Antarctic ice sheet is the largest remnant of previous ice-age glaciations. Glaciers flow out from this ice sheet and feed into floating ice shelves along one-third of the Antarctic coastline. One of the largest ice shelves is the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf, located on the southeastern edge of Antarctica's Weddell Sea and covering more than 415,000 square kilometers (160,000 square miles). During an exploratory borehole survey undertaken in 2017 to collect seafloor sediment samples, geologists made an unusual discovery. After drilling through the 900-meter-thick (2950-foot-thick) ice shelf, the scientists lowered a sediment coring device with an attached video camera through the borehole and then down another 490 meters (1600 feet) of seawater, hoping to reach the seabed mud below the ice shelf. However, instead of hitting the seafloor, the coring device struck a large boulder. Subsequent video footage revealed that the boulder was covered by numerous sessile (stationary) marine species, including sponges (both stalked and nonstalked types) and other likely filter-feeding invertebrates. See also: Antarctic Ocean; Antarctica; Deep-sea fauna; Glaciology; Marine sediments; Porifera; Sea ice

Until now, the prevailing belief was that deep-sea life under ice shelves is scant. The conditions below ice shelves are extremely harsh, being aphotic, or without light (thus, organisms living beneath ice shelves are incapable of photosynthesis), and with below-freezing temperatures of around –2.2°C (28°F). As such, only a few animals—mostly small, mobile invertebrates, including worms, jellyfish, and krill—have ever been observed previously in habitats below ice shelves. Deep-sea, sessile, filter-feeding animals, such as sponges, were expected to be extremely rare or nonexistent because these organisms depend on food material (detritus) originating from organisms living close (or closer) to the surface of the open ocean (which is often located hundreds of kilometers away from ice shelves) and floating along deep-sea ocean currents. However, the existence of a community of sessile organisms attached to a hard substrate beneath the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf indicates that this type of habitat is not, after all, a marine desert. Scientists are interested in studying the distinctive biological adaptations that have enabled these animals to live under such extreme conditions. In addition, as these organisms are located very distant from any potential food sources, it is probable that they are well adapted to seasonal or otherwise highly intermittent food supplies. See also: Adaptation (biology); Ecological communities; Marine ecology; Photosynthesis

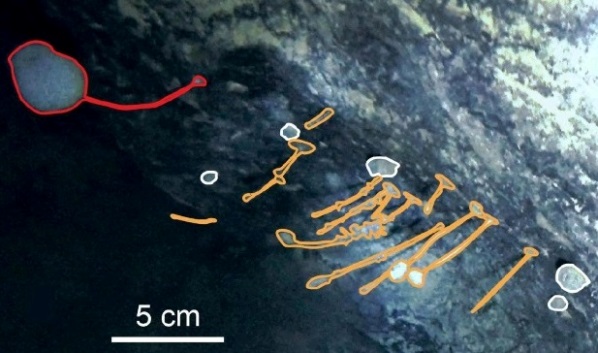

Biologists are somewhat perplexed about the origins and survival capabilities of sessile, sub–ice shelf communities. It is surmised that sessile animals living below the ice shelf probably drifted as planktonic larvae for distances as great as hundreds of kilometers, subsequently attached to the hard substrate, and then grew into adult forms. In addition to sponges, the organisms detected beneath the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf include undetermined stalked taxa (possibly other sponges, or ascidians, hydroids, or barnacles). However, until actual specimens are collected by investigators, it is impossible to determine their phylogeny. In other words, it is not known if the taxa are similar to those found elsewhere in the open ocean, or if they have evolved unique abilities to inhabit their present location beneath the ice shelf. It is even possible that the sponges and other deep-sea taxa that have been detected belong to previously unknown species. In the near-future, investigators hope to send an underwater vehicle or collecting device to the area below the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf in order to obtain physical specimens for further study. See also: Animal evolution; Evolution; Phylogeny; Speciation; Underwater vehicles