The ice-covered moon Europa has long intrigued researchers as a potential abode for extraterrestrial life. Although its orbit around Jupiter is frigidly far from the Sun, Europa harbors an internal ocean. Furthermore, this inner liquid reservoir likely receives warming energy due to gravitational interactions amongst Jupiter and its numerous moons. Understandably keen to study Europa's innards, scientists have pinned their hopes on a future robotic lander that might drill through the moon's frozen shell. New findings from an old spacecraft, however, have strongly indicated that plumes of material can escape from Europa's inner ocean into space, offering a far simpler way to learn Europa's secrets. See also: Gravity; Jupiter; Ocean; Sun

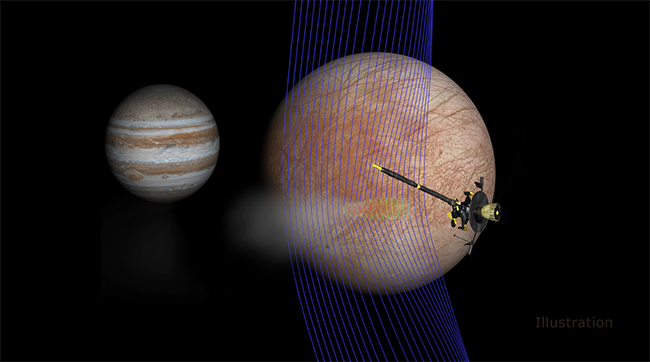

The Galileo spacecraft and probe arrived in the Jovian system in 1995, completing 34 orbits of Jupiter and its natural satellites before mission's end in 2003. In 1997, during one of Galileo's closest swoops past Europa, the spacecraft's instruments registered a bend in the local magnetic field and an increase in plasma density. At the time, researchers could not attribute the readings to any known phenomena. Subsequent observations in ultraviolet light by the Hubble Space Telescope, though, hinted at plumes of water vapor rising off Europa. Recently, astronomers realized that Galileo had collected its data in a region above Europa linked to Hubble's potential plumes. Comparing all the data to a new, sophisticated computer simulation supported the plume model, with all signs pointing to Galileo having serendipitously flown through such an outburst two decades prior. The source of the plumes is unknown, but possibilities include the sort of hydrothermal activity that spawns Earthly geysers. See also: Earth; Galileo mission; Geyser; Hubble Space Telescope; Hydrothermal vent; Plasma (physics); Ultraviolet astronomy; Ultraviolet radiation; Water

The finding is a boon for the next mission slated to study the Jovian moon up close. Called the Europa Clipper, the space probe is slated to launch as early as 2022. It will make much closer passes than Galileo, coming within about 25 km miles (16 mi) of the Europian surface compared to Galileo's approximately 400 km (250 mi), and thus will be in position to sample frozen particles and dust in less diffuse portions of the plumes. In this way, scientists will be able to obtain direct insight into whether the moon contains the ingredients for life. Even if the moon does not contain these essential ingredients, another plume-spewing moon—Enceladus, in orbit around Saturn—could still offer another tantalizing target, alongside Mars, in the search for extraterrestrial life right here in our solar system. See also: Astrobiology; Biology; Climate history; Enceladus; Extraterrestrial intelligence; Mars; Saturn; Solar system