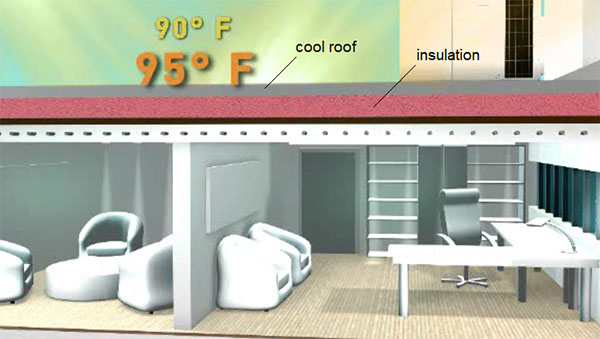

In the journal Science (September 2018), researchers reported a method for making a coating that reflects sunlight and radiates heat. The coating can be used to cool buildings and reduce air-conditioning use, keeping surfaces painted with the material about 6 degrees Celsius cooler than the surrounding air temperature. The paint can be easily applied to most surfaces, including the exterior walls and roofs of existing buildings. The cooling effect is based on a phenomenon known as passive daytime radiative cooling, whereby a surface cools without any energy input by reflecting ultraviolet to near-infrared solar radiation (278- to 4600-nanometer wavelengths) and radiating long-wave radiation (8000- to 13,000-nanometer wavelengths) through the atmosphere to outer space. Cool roofs designed using metals (such as aluminum) or white-pigmented paints help keep building temperatures lower by reflecting sunlight but are less effective at emitting the heat they absorb because heat is reflected inside these materials. See also: Buildings; Emissivity; Heat transfer; Infrared radiation; Paint and coatings; Radiation; Reflection of electromagnetic radiation; Solar radiation

Simple in composition and method, the new cooling paint consists of a commercially available polymer, called poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropene), a solvent (acetone), and a small amount of water. When a coat of paint is applied to a surface, the acetone evaporates first, leaving behind droplets of water dispersed in the polymer which, after evaporating, creates a porous, sponge-like-structured (phase-inversion) coating that reflects up to 99.6 percent of incoming sunlight and emits heat in the infrared range known as the long-wave infrared (LWIR) transmission window, a region of the electromagnetic spectrum at which heat is transmitted directly to space without warming the atmosphere. The researchers said that this phase-inversion-based method is suitable for use with other polymers and solvents, enabling the production of customized coatings, such as glossy coatings or coatings for higher operating temperatures. See also: Acetone; Electromagnetic radiation; Polyfluoroolefin resins

At present, in the United States, air conditioners use about six percent of all the electricity produced, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. By 2050, the demand for energy for air-conditioning is expected to triple worldwide, according to the International Energy Agency. Adding to the problem, air conditioners vent hot air outside, making the outdoor air warmer, particularly in cities at night. As the global climate warms, producing more energy-efficient air conditioners will help slow the increase in energy use. However, combining that approach with passive daytime radiative cooling paints could result in even more energy-efficient buildings. See also: Air conditioning; Architectural engineering; Deadly heat in an era of global climate change