Key Concepts

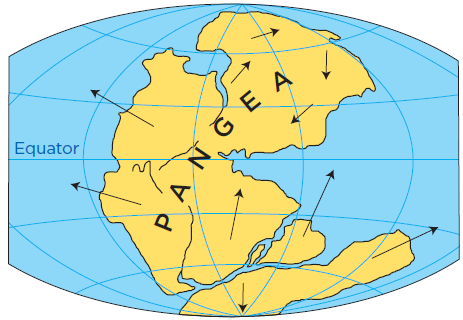

The concept that the world's continents once formed part of a single mass and have since drifted into their present positions.The fundamental concept is that not only have the continents drifted, but the continents are merely parts of thicker tectonic plates, comprising both oceanic and continental crust, with 50–300 km (31–186 mi) of the Earth's mantle moving along with them. See also: Continent; Plate tectonics

Historical evidence

Although continental drift was outlined by Alfred Wegener in 1912, the idea was not particularly new. Paleontological studies had already demonstrated such strong similarities between the flora and fauna of the southern continents between 300,000,000 and 150,000,000 years ago that a huge supercontinent, Pangea, had been proposed (see illustration). See also: Paleontology; Supercontinent

Wegener's ideas were almost universally rejected at a meeting of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists in 1928. His evidence and timing were undoubtedly wrong in many instances, and only a few scientists accepted his general concepts and remained sympathetic to the ideas. The fundamental objection was the lack of a suitable mechanism. Studies of the passage of earthquake waves through the Earth had shown that, whereas the core is liquid, the Earth's mantle and crust are solid. It was therefore difficult to find sufficient force to move the continents through the mantle and oceanic crust, and even more difficult to picture them moving without leaving obvious evidence of their passage.

Almost simultaneously with the temporary eclipse of Wegener's theory, Arthur Holmes was considering a mechanism that is still widely accepted. With the knowledge that radioactive minerals occurring within the Earth could result in an internal zone of slippage, Holmes conceived the idea of convective currents within the Earth's mantle which were driven by the radiogenic heat produced by radioactive minerals within the mantle. Since the rates of motion were slow, but vast and inexorable, the Earth appeared solid to the rapid passage of seismic waves, but behaved plastically to such slow motions. This accounted for the apparent discrepancy between the seismic observations and the drift of continents. At that time, Holmes's ideas, like those of Wegener, were largely ignored, as it was no longer thought that continental drift was worthy of further consideration. Nonetheless, several geologists, particularly those living in the Southern Hemisphere, continued to believe the theory and accumulate more data in its support, particularly from the study of the similarities in fossils and rock types on now separated continents. See also: Convection in the Earth; Radioactive minerals; Seismology

Convincing evidence

From 1950 to the 1970s, convincing evidence accumulated, with studies of the magnetization of rocks, paleomagnetism, beginning to provide numerical parameters on the past latitude and orientation of the continental blocks. Early work in North America and Europe clearly indicated how these continents had once been contiguous and had since separated. The discovery of the mid-oceanic ridge system also provided more evidence for the geometric matching of continental edges, but the discovery of magnetic anomalies parallel to these ridges and their interpretation in terms of sea-floor spreading finally led to almost universal acceptance of continental drift as a reality. Since the acceptance of continental drift, the interest has changed from proving the reality of the concept to applying it to the geologic record, leading to a greater understanding of how the Earth has evolved through time. See also: Earth's crust; Evolution of the continents; Geodynamics; Mid-Oceanic Ridge; Paleomagnetism