Key Concepts

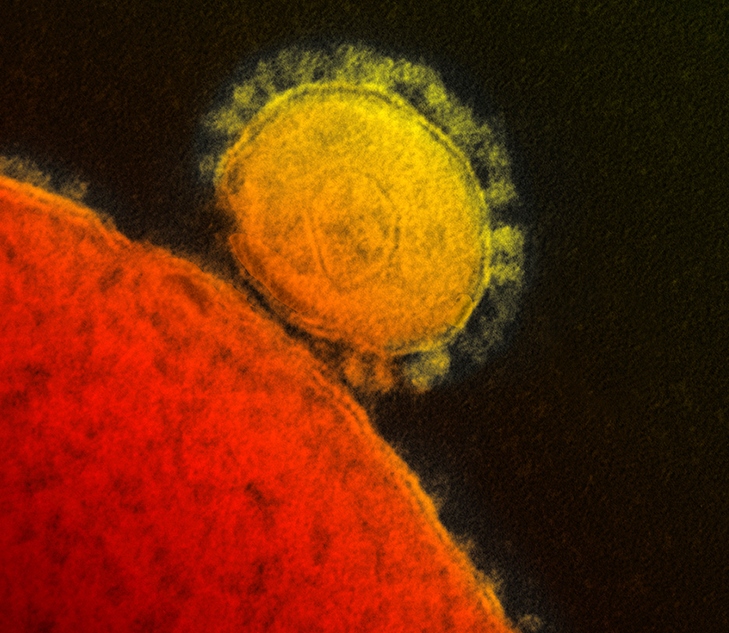

A viral respiratory illness caused by the MERS coronavirus, principally occurring in the Arabian Peninsula. Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is a contagious, often fatal, respiratory illness. The causative agent is a specific type of coronavirus termed the MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV) [Fig. 1]. The virus and the disease were initially identified in Saudi Arabia in 2012. Since then, more than 2500 cases and 860 deaths have been reported, predominantly in or near the Arabian Peninsula. Overwhelmingly, most cases and deaths due to MERS have occurred in Saudi Arabia. Typical symptoms of affected individuals include fever, cough, shortness of breath, and pneumonia (this latter symptom may be absent in some cases). The case fatality rate of patients with MERS-CoV infection is approximately 34%. See also: Clinical microbiology; Coronavirus; Detection of respiratory viruses; Epidemic; Infectious disease; Respiratory system disorders; Virus; Virus classification

Background

The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) pandemic that occurred in 2002–2003 was caused by a coronavirus (SARS-CoV). The name coronavirus (Latin corona, meaning crown or a halo appearance) comes from the shape of the virus when it is observed using an electron microscope. Coronaviruses typically infect mammals and birds, and the SARS outbreak was initially associated with live-animal marketplaces in China. Only a handful of coronaviruses cause disease in humans—for example, SARS-CoV (which caused the aforementioned 2002–2003 outbreak) and SARS-CoV-2 (the causative agent of the COVID-19 pandemic, which began in 2019 in China and spread globally in 2020). However, in 2012, another new human coronavirus, that is, MERS-CoV, emerged in Saudi Arabia. See also: Novel coronavirus is declared a global pandemic; Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)

Epidemiology of MERS

The initial human cases of MERS infection originated in the Arabian Peninsula. The average age of the laboratory-confirmed cases was 60 years. Forty-two (21%) of the cases were health-care workers. Despite this evidence of person-to-person transmission, the number of contacts infected by persons with laboratory-confirmed infections has been very low. The World Health Organization (WHO) was confident enough in the global response to MERS that no travel restrictions were imposed on pilgrims traveling to Saudi Arabia for the Hajj, which is one of the largest mass gatherings of Muslim people in the world (Fig. 2). See also: Epidemiology

Investigations have continued to search for an animal reservoir of the MERS-CoV. Researchers have found that the MERS-CoV could replicate in various bat cell lines. In addition, several teams of researchers have collaborated to collect blood samples from camels (Fig. 3), goats, sheep, and cattle in the Middle East (Oman), Spain, the Netherlands, and Chile. They discovered that 100% of the blood samples from camels in Oman and 14% of the blood samples from Spanish camels contained neutralizing antibodies (that is, antibodies that reduce or abolish some biological activity of a soluble antigen or of a living microorganism) against the MERS-CoV, indicating infection with or exposure to the new virus. Blood samples from European sheep, goats, and cattle did not contain antibodies. Additional studies have found antibodies against the MERS-CoV in camels in Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the Canary Islands. These results suggest that MERS-CoV or a related virus infected the camel populations; thus, camels may constitute a possible animal reservoir of the virus. Of the initial 203 human cases of MERS, 7 had confirmed contact with camels. See also: Camel; Disease ecology; Neutralizing antibody; Zoonoses

Other studies on archived camel blood samples originally collected from 1992 to 2010 in Saudi Arabia have determined that MERS-related coronaviruses have been circulating in camels countrywide since at least 1992. The research team also screened blood samples from sheep and goats, but found no evidence of MERS-CoV infections in these animals. It is not known whether human infections with the MERS-CoV occurred before 2012 because diagnostic tests were not yet available. The only way to answer this question would be to screen archived samples of human blood to determine when a cross-species zoonotic transmission from camels to humans occurred.

Transmission

MERS-CoV is transmitted via an infected person's respiratory secretions (for example, when coughing). Although MERS-CoV has spread from affected individuals to others through close contact (including close contact with personnel in health-care settings), there have been no reports of sustained community spreading of the MERS-CoV. For the most part, the disease has been confined to areas of the Arabian Peninsula. However, small numbers of travel-associated cases have occurred outside of the Middle East, including Europe, the United States, and eastern regions of Asia.

Most individuals who are infected with the MERS-CoV display mild symptons, including fever and cough. Severe respiratory illness (including pneumonia) and kidney failure occur in more-critical cases. In addition, individuals with preexisting medical conditions or weakened immune systems are more susceptible to develop serious illness.

Treatment and prevention

No vaccine is available to protect people from contracting MERS. Individuals who are infected by the MERS-CoV are given medical treatments to help relieve symptoms. In more-severe cases, preservation of organ function is essential. For epidemiologists, the main goal of scientists has been to stop the spread of the MERS illness whenever isolated cases arise. See also: Public health; Vaccination